As a child, I listened to my father’s stories of his boyhood in 1950s Czechoslovakia, stories of adventures taking place in the cobblestoned streets of his hometown or near the fields of his grandparents’ village. I never met any of his family, in life or in photographs. And by the time I was born, the streets and buildings that came alive in his descriptions were gone. They were demolished along with eighty other towns in the area to make way for expanding coal mines. With no way to connect my father’s memories to physical locations or images, the stories I heard sounded like make-believe, no more real than the tales I read in my storybooks.

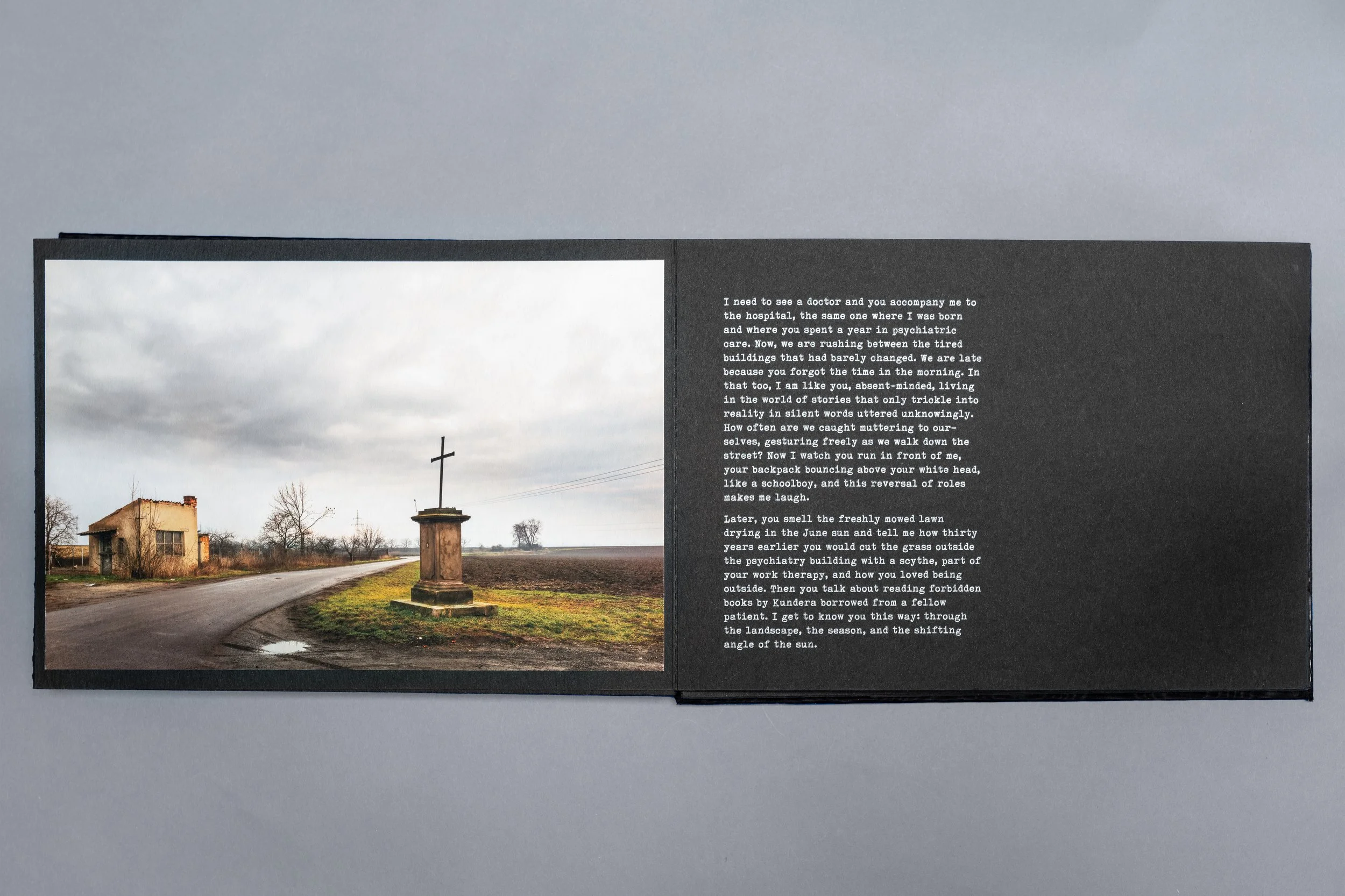

Driven by a need to fill the voids in family history and geography, I returned to the north Bohemian city of Most, where both my father and I were born, and retraced the locations of former towns. Guided by historical maps, my father’s memories, and above all by the landscape itself, I searched for clues that would reveal what was no longer there. Frequently, my father joined me on my expeditions, and as we walked or traveled by local trains and buses, he shared stories from personal history and geography—guiding me at once through the present and the past.

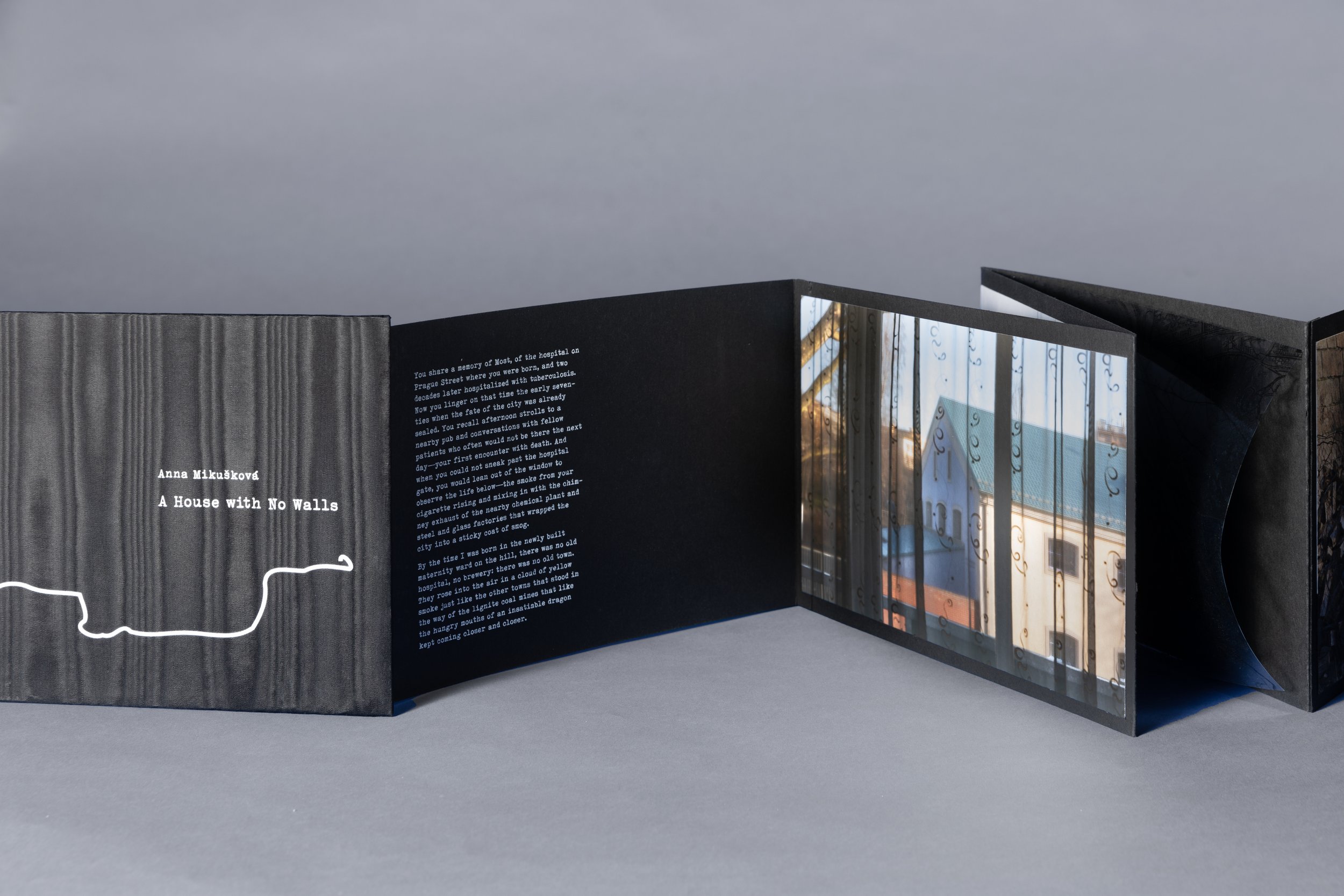

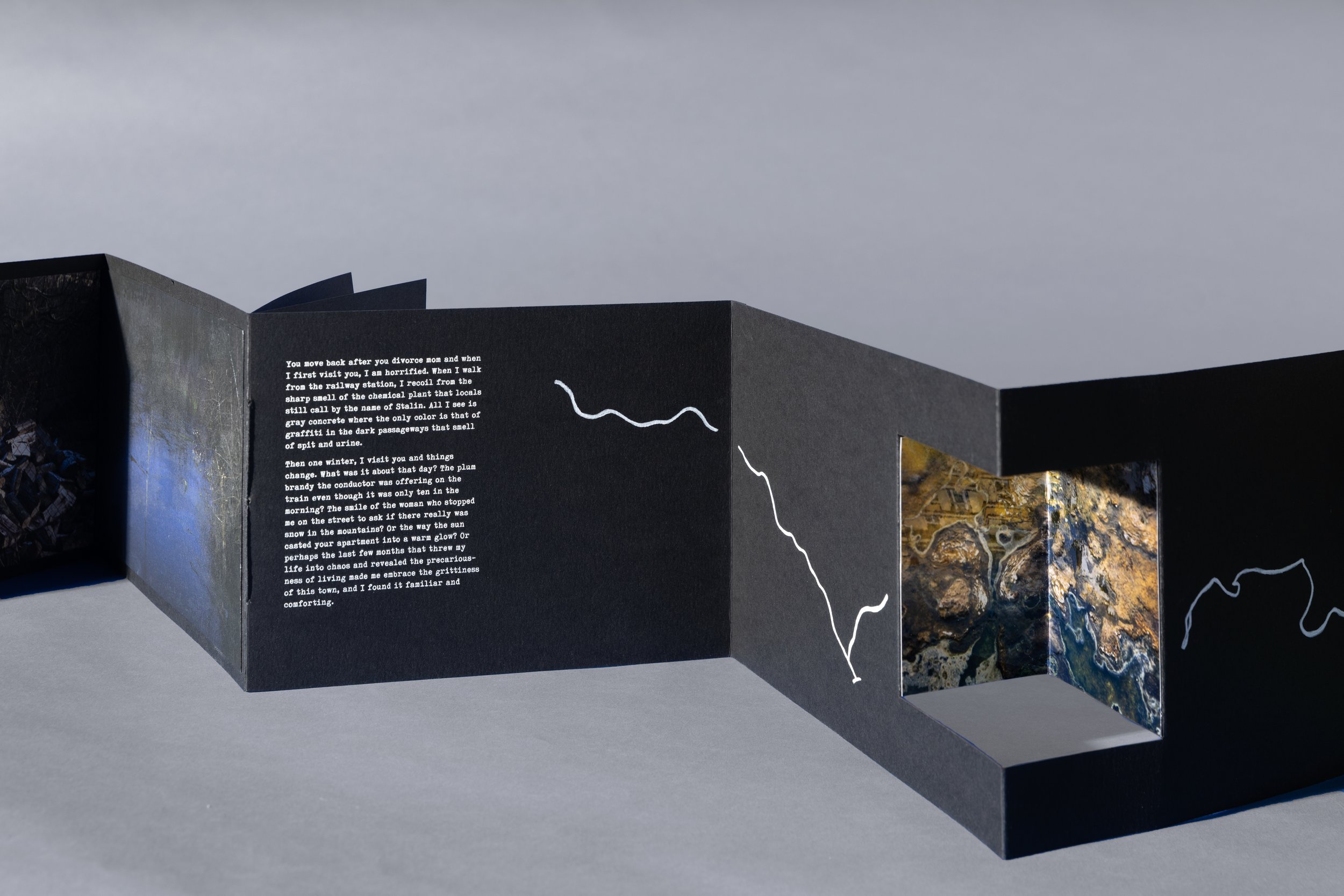

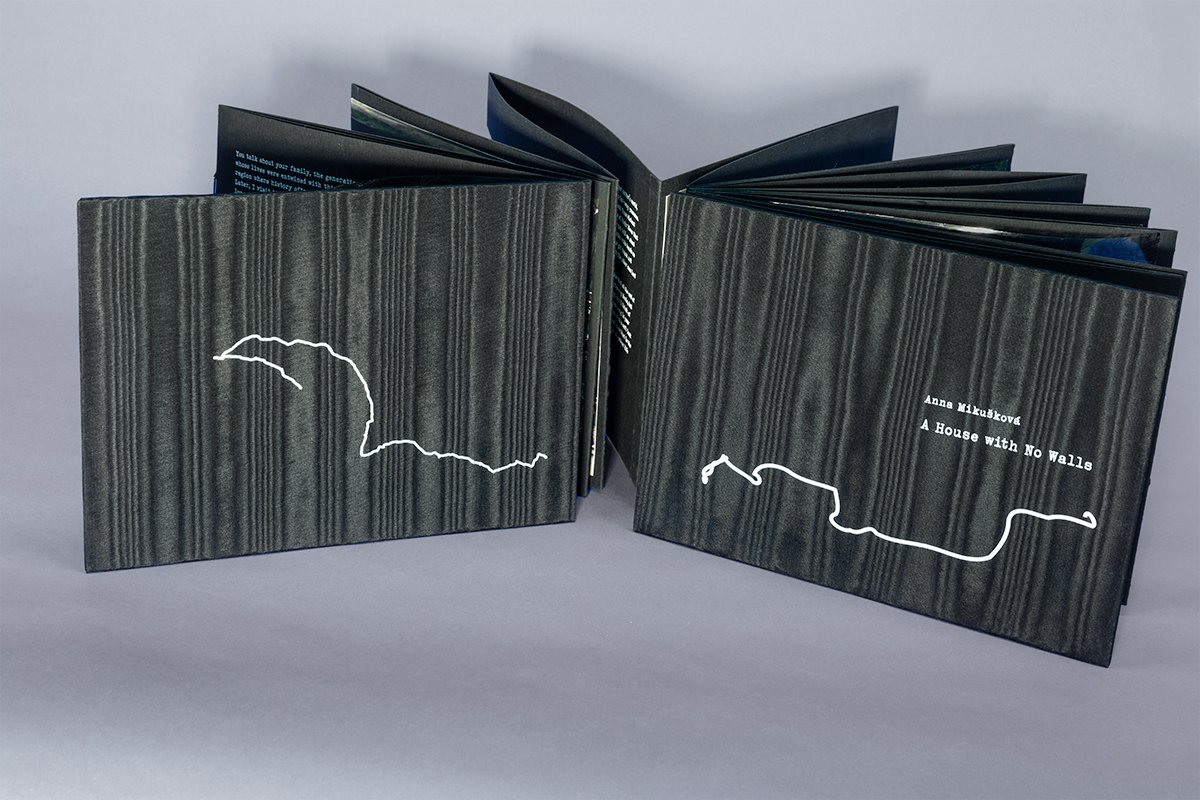

“I am not a poet, I am a city, ill-equipped to write about the affairs of people. I am a city, a new city. I cannot bear witness to the past” writes the Czech poet Pavel Brycz about the town of Most. A House with No Walls describes what I see and bears witness to the past with a combination of photographs, historical maps, routes of my walks, and text addressed to my father. While the photographs of suggest an interplay of presence and absence and the ability of landscape to simultaneously obliterate history and reveal it, the historical maps printed on transparencies point to the transitory nature of cartographic practices in a location subject to frequent border changing. Together, these elements speak to the difficulty of photographically representing the past and suggest an alternative mapping of history and geography. Offering an interactive experience through accordion binding, foldouts, and map overlays, A House with No Walls invites readers to walk through a real and imaginary landscape and consider the fractured identities in regions and lives affected by resource extraction and the impermanence of our concept of home.

Watch an excerpt from Most —the Most Beautiful Town, which shows the town of Most throughout the second half of the 20th century, including the demolition of the old town where my father was born and the development of the “New Most,” where I was born.