Heart of Darkness, Fountain of Gold: Notes from Antarctica

“Over the years, one comes to measure a place, too, not just for the beauty it may give, the balminess of its breezes, the insouciance and relaxation it encourages, the sublime pleasures it offers, but for what it teaches. The way in which it alters our perception of the human. It is not so much that you want to return to indifferent or difficult places, but that you want not to forget. If you returned it would be to pay your respects, for not being welcomed”.

Informed by Indifference: A Walk in Antarctica, Barry Lopez

8/26

August, the outer edge of winter. Indigo-blue dawns signal the end of the sunless polar night. I move into a dorm: a bed, a lamp, a metal locker, a corner divided from others by a cotton sheet. Outside, my meanderings are limited by the boundary of the island, by the climate, the weather, the restrictions of my body on a continent inhospitable to humans.

As I absorb the peculiar rhythms of this foreign landscape, my fundamental assumptions about time, seasons, laws of physics, the interplay of light and shadow are challenged. In a radius of a few miles, the contours of my known world constrict and expand at the same time.

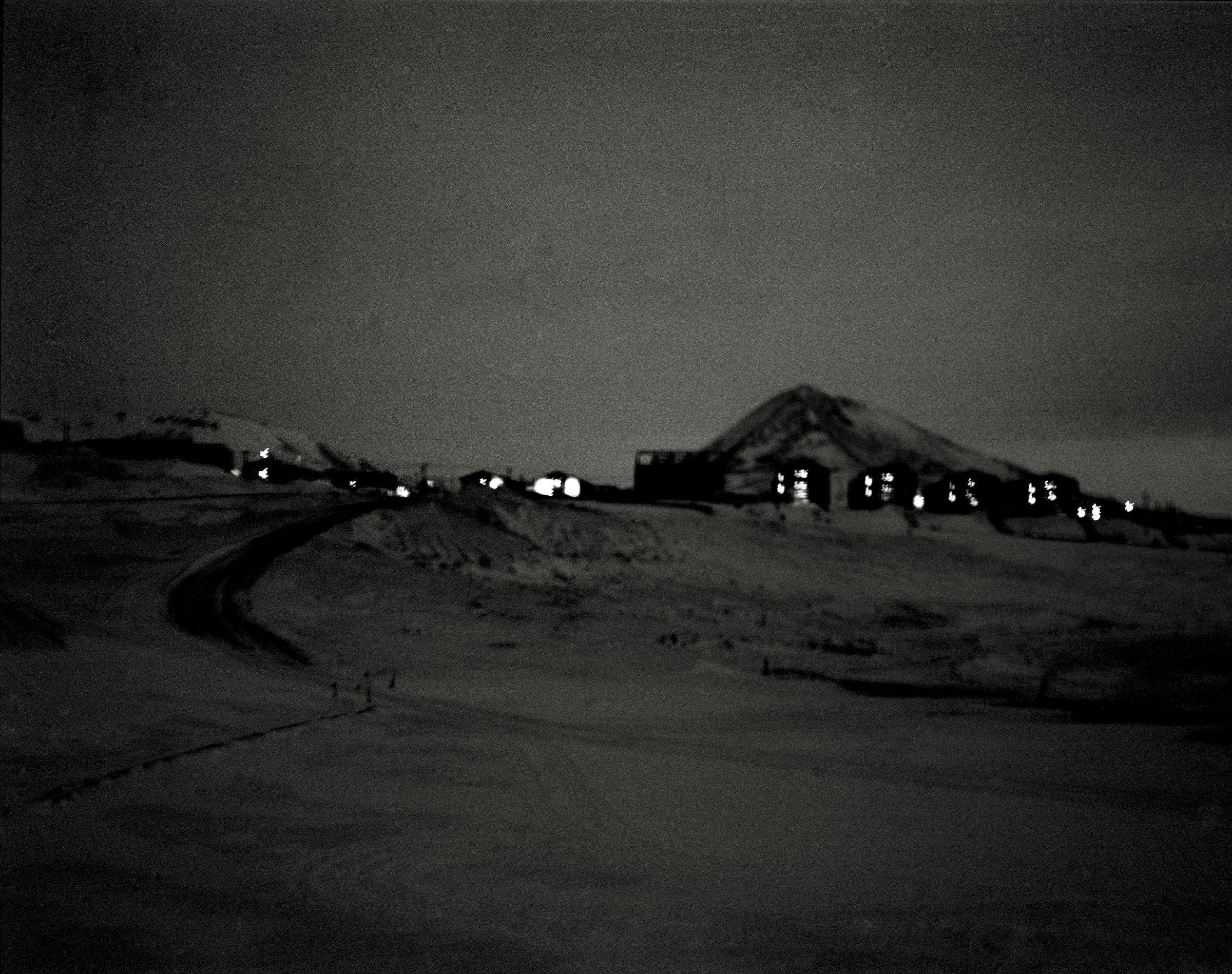

The Transantarctic Mountains, September 2024, Ilford HP5

9/5/24

I begin to know the island in the dark, on the first hesitant walks through town, its outlines revealed by the dim light that lingers on the horizon for hours after the newly arrived sun sinks below it. My steps are heavy, weighted down by the cold weather gear, by the clunky bunny boots. My muscles contract as I swim through the dense current of air that sweeps through the streets gaining strength near the sea, its edge obscured by frost. Under my feet, the ice moans and grumbles. Even through the thickness of my soles, I feel its sharp edges. Sastrugi—a word like a whisper, like a murmur of the hungry wind when it quiets down for just a breath before spinning into a howling force that can befog a mind already muddled by frost.

My fingers go numb. Eyelashes stick together, bonded by rime. Tears well in my eyes. And yet, I am mesmerized by the darkness. By the sharpness of the cold. By the solitude of the night.

At times, I raise my hand and trace the contours of the volcanic hills that surround the town. Even in the darkness, I can make out the slope of their gentle curves. With my sight compromised, I come to know the island with all my senses. For months afterward, my body retains its wordless knowledge.

12/1/2024

I had put off recording the sound of ice until there was none beneath my feet. Like many others, I made the mistake of expecting my new landscape would remain the same: white, frozen, still. This image is so prevalent that we cling to it even here. Disregarding the dynamic complexity of the ecosystem, we hold onto our idea of Antarctica mediated by images that portray the continent as colorless, harsh, as the “coldest, driest, windiest on Earth”— a narrative that leaves little room for nuances.

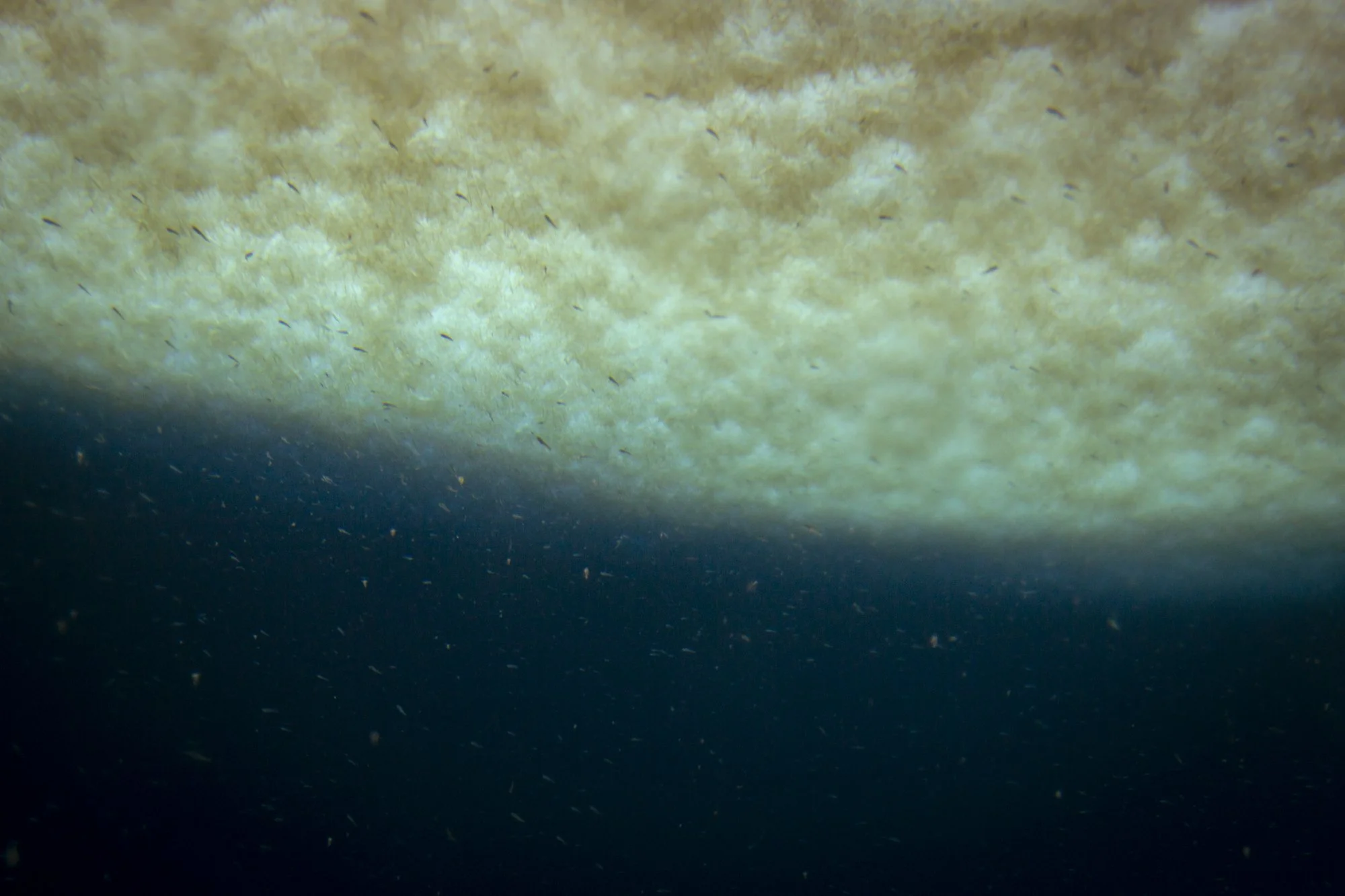

Before I arrived, I heard of dwindling colonies of penguins, calved icebergs, and melting ice sheets. I read stories of a few white men who strived to be the first, sometimes paying for their ambition with their lives. I saw countless images of ice. But I did not know what it is like to experience the transition of a frozen ocean to open water—an ocean frozen so solid you cannot tell its edge from the ground beneath your feet. I did not know what it is like to stand on its shores and after months smell the sea and listen to the soft waves wash out, see the first skuas dart into the sky, and weeks later observe their young ones attempt their own flight. I could not imagine the sublime moment when a Weddell seal swims past the shore, perhaps alone for the first time since weaning her young one. In December, her body is still recovering from the six weeks of nursing when she transfers a significant amount of weight and nutrients to her pup. Unable to stay underwater for as long as before, she frequently resurfaces for air. For a brief moment, her brown round eyes meet mine before her body becomes one with the darkness of the sea and I am left breathless on the shore, suddenly aware of my aloneness. To hear her soft exhale as she emerges above water, graceful, humanlike, to experience even here at 77 degrees South the cycle of life, feels nothing short of miraculous.

McMurdo, September 2024, Ilford HP5

12/8/2024

In the lab, I touch the smooth surface of a 400,000-year-old ice core—layers and layers of ice compressed by time. Inside, tiny pockets of air contain an atmosphere from an age long before us. In my hands, I hold a volcanic crystal formed deep beneath Mount Erebus. In an aquarium tank, I stroke the urchins and sea lemons retrieved from the Southern Ocean by Antarctica divers—the few fortunate to experience the depths hidden underneath the surface of the ice.

Gradually, my understanding of Antarctica shifts from seeing it as remote and singular, as vastly different from the world I am familiar with, to seeing its place in a network of much wider forces than I am used to considering. To understanding how this continent holds onto geological time far beyond human presence, to sensing its connection to other planets. Under my feet lies a depthless archive of the Earth, thousands of years preserved in the layers of ice, in the rocks, in the volcanic ash, in the bones and feathers buried within them, in the particles of crystalized gold emitted from Mount Erebus and scattered across the ground.

Southern Ocean, November 2024, Ilford HP5

2/20/2025

I glance for one last time over the landscape that, for a blink of an eye, was my home. It is raw and rudimentary, stripped of all the color and embellishment that comes with flora that once covered even this continent. Lush ferns, sky-high conifers, tropical palm trees—all of them gradually freezing away, leaving Antarctica bare, stripped down to the very essentials that can still form the mass beneath our feet: rocks and ice. Even the birds and mammals wear the colors of the landscape as if not to disturb the simple harmony of shape and form and the wide-open spaces in between that show us what often remains invisible: the air and the wind. Here, you truly must dive deep to discover the vibrant richness hidden underneath.

I think of the divers sometimes, see them floating through the blue-green depths, past the electric yellow of sea lemons, the orange hues of sea stars, or earth-red urchins before they emerge back into the world of a hundred shades of white. White, cream, blue, pink, mauve, purple, nectarine, brass—all reflected in the vast expanse of ice that guards ancient secrets about Earth’s past simultaneously giving us a glimpse into its future. By going back, we move forward.

As I leave, I think of all my hikes to Castle Rock and Hut Point, of the joy that comes with discovery and slowly learning a place through thousands of steps until one day I stand at Vince’s cross, and when I look at the Sound and the hodgepodged town below, I realize they have become known to me and so much dearer for this knowledge. And yet, for all our knowing, there are still so many mysteries to uncover. Antarctica holds tight to its secrets. Or perhaps not. Perhaps they are all out there in the open but lie just a few inches beyond our ability to record, analyze, and comprehend. And so, we must keep on exploring.

Southern Ocean, January 2025,